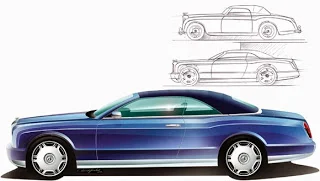

Returning Bentley CEO Wolfgang Dürheimer, it seems, waxes nostalgic for a convertible. He’d like to build a 2-seater but he’ll most likely follow Royce’s example and go for a 4-seater. He liked the 1995 Azure, which continued in various iterations for years. His options now, with W12, V8 and V10s available from stock, as it were, are wide and the Continental is a fine platform.

recalled the first Azure (left).

By 1995, after the best part of a quarter-century, the Corniche-Continental’s time was up. When they drew up Project 90 in 1985, THE COMPLETE BENTLEY ebook

(below)

which had evolved into the Continental R, Heffernan and Greenley conceived a convertible which as a result had been waiting ten years. Despite a good deal of strengthening and reinforcement, scuttle shake was endemic in the old Corniche, so it had to be done away with for the Azure. Basing it on the Continental R instead of the old Corniche brought a 25 per cent improvement in torsional stiffness.

Manufacture however was not straightforward. A joint project was arranged between Crewe and Pininfarina in Turin under which Park Sheet Metal in Coventry, which made Continental R body shells, sent sub-assemblies to Italy for completed bodies to be painted and have the intricate power-operated hood mechanism fitted by specialist Opac before being shipped back to Crewe for completion. Bodybuilding was done at Pininfarina’s San Giorgio Canavese factory, where Cadillac Allantes had been put together. The unitary hulls still had to be strengthened to make up for the absence of a roof, with an additional 190kg (418.9lb) of reinforcement under the rear floor, deeper door sills, thicker A-posts and screen top rail.

All that remained of the Corniche’s shivers, I recall from a 1995 road test, were tremors that could still be seen in the rear-view mirror and vibrations felt through the steering column. Door sill plates proclaimed Bentley Motors’ and Pininfarina credit for the structure, in particular the power hood designed to close in 30sec, although one famously failed on the Cote d’Azur press launch. The Azure’s interior was furnished like the Continental R with traditional veneers and leather, woollen fleeces on the floor and, by virtue of a 1992 co-operative agreement with BMW, electrically operated front seats with integral seat belts from the 8-series coupe.

Final Azure 2005

Several generations of fast turbocharged Bentleys had transformed road behaviour, from the early tentative 1970s when Bentleys carried the legacy of Rolls-Royce town carriages, to the dawn of the 21st century when they were more able to compete with fast rivals. Steering was now 2.9 turns from lock to lock, faster, sharper, with more feel; braking more progressive with ever-bigger discs, and body roll, although by no means eliminated was less pronounced.

INTRODUCTION Geneva 1995.BODY Convertible; 2-doors, 4 -seats; weight 2610kg (5754lb);

ENGINE V8-cylinders, in-line; front; 104.1mm x 99.1mm, 6750cc; compr 8:1; 286kW (383.53bhp) @ 4000rpm; 42.4kW (56.86bhp)/l; 750Nm (553lbft) @ 2000rpm. ENGINE STRUCTURE pushrod overhead valves; hydraulic tappets; gear-driven central cast iron camshaft; aluminium silicon cylinder head; steel valve seats, aluminium-silicon block; cast iron wet cylinder liners; Garrett AiResearch TO4 turbocharger .5bar (7.25psi); intercooler; Zytek EMS3 motormanagement; 5-bearing chrome molybdenum crankshaft. TRANSMISSION rear wheel drive; GM turbo Hydramatic 4-speed; final drive 2.69:1

CHASSIS steel monocoque, front and rear sub-frames; independent front suspension by coil springs and wishbones; anti roll bar; independent rear suspension by coil springs and semi-trailing arms; Panhard rod stiffener; anti roll bar; three-stage electronically controlled telescopic dampers and Boge pressure hydraulic self-levelling; hydraulic servo brakes, 27.94cm (11in) dia discs front ventilated; twin circuit; Bosch ABS; rack and pinion PAS; l08l (23.75gal) fuel tank; 255/55-WR 17 tyres, 7.6in rims, cast alloy wheels DIMENSIONS wheelbase 306cm (120.47in); track 155cm (61.02in); length 534cm (210.24in); width 188cm (74.02in); height 146cm (57.48in); ground clearance 14cm (5.5in); turning circle 13.1m (42.98ft).EQUIPMENT 2-level air conditioning, leather upholstery, pile carpet, 8-way electric seat adjustment, galvanised underbody PERFORMANCE maximum speed 249kph (155.1mph); 64kph (39.87mph) @ 1000rpm; 0-100kph (62mph) 6.0sec; fuel consumption 19.3l/100km (14.64mpg) PRICE £215,000 PRODUCTION 1311

PICTURES above right 2003 Limited Azure edition. Left Road test GTC chez nous