Fifty years ago this week I set off from Spa in Belgium to report the last Spa-Sofia-Liège Rally. The Marathon de la Route was organised by the Royal Motor Union of Liège, whose M Garot enjoyed his reputation for organising the toughest rally in the world. Started in 1931 as the Liège-Rome-Liège, it had been to various turning points, settling in 1964 on Bulgaria then well behind the Iron Curtain. Only a handful of cars ever made it to the finish.

I set off from Spa in pursuit. The Motor sent junior staff on important assignments safe in the knowledge that they were accompanied by veteran photographers. They, like George Moore who came with me, had done it all before. We could pitch up at a Yugoslav B&B; George would know the language, how much we’d be charged and probably the proprietor’s name. He introduced me to drivers, team managers, other journalists and helped me across the tripwires of providing a true and accurate account, without frightening the horses.

You would be meeting them again on the RAC and then the Monte as well as next year’s Alpine. They seemed to run out of Presse plates so I ran as an Officiel.

A Ford Corsair GT was unlikely as a means of keeping up with works Austin-Healey 3000s and 1962 European Rally Champion Eugen Böhringer, but it was the only car spare. It could manage 95mph on a good day and reach 60 inside 13sec. In the interests of science I made the brakes fade on the downside of an alp; I had heard about brake fade but never really experienced it so when George dozed off I got the brake fluid boiling. The 9in front discs (there were drums at the back) were probably aglow. I left off before it got dangerous.

We kept up with the rally for 3,000 miles. George knew the shortcuts when it dashed off into the mountains. Memorably this was the event on which Logan Morrison and Johnstone Syer, whom I knew from Scottish rallies, retired their works Rover 2000 when Blomquist’s Volks-wagen overturned. The driver was unconscious and nobody, not even a VW team-mate, had stopped so Logan's opportunity for glory was lost.

This was also the rally on which BMC competitions manager Stuart Turner could not conceal his delight. He had not only scored the second win with a big Healey but also “We broke the sound barrier - we got a Mini to the finish of the Liège.”

Title of the report? The Beatles had just made “A Hard Day’s Night.” Aaltonen’s car (below left) was sold by Bonhams in 2005 for £100,500. I drove another works car in 1966, reporting on it in Safety Fast magazine and again in

Amazon £3.08. After a number of countries decided rallies at such speeds dangerous, they refused the Royal Motor Union permission to continue it. The Marathon de la Route became a track event on the Nürburgring. The Liège-Rome-Liège reappeared only as a touring classic.

The Motor, week ending September 5 1964

A hard (four) days’ night. Austin-Healey win an even faster Spa-Sofia-Liège rally. Report by Eric Dymock pictures by George Moore.

“The Liège has been getting slack; there were twenty five finishers last year and eighteen the year before.” In 1961 there were eight, thirteen in 1960 and fourteen the year before that. M. Garot wants it back to about eight and this year he very nearly got his wish until an alteration in plans put several cars back into the running. But he tried.

After the finish, John Sprinzel said, “This year we did about a day and a half's route in a day.” The pace was much, much hotter with average speeds of 50 and 60 mph over rough, rocky roads where such a schedule is just not possible. The 1964 Spa-Sofia-Liège was run in hot weather over roads little rougher than before but at a cracking, damaging pace for four days and nights of the most intensive high-speed motoring in the world.

RaunoAaltonen, the Finnish speedboat racer and Tony Ambrose, Hampshire shopkeeper, won with a works Austin-Healey 3000. Saabs driven by Erik Carlsson and Pat Moss-Carlsson were second and fourth, and Eugene Böhringer took third place in a 230SL Mercedes-Benz after two successive wins in 1962 and 1963. For finishing in three consecutive years, Böhringer wins a Gold Cup in company, this year, with Paul Colteloni (Citroën), Francis Charlier (Volvo) and Bill Bengry (Rover two years, now Sunbeam).

Citroën were the only manufacturer with a team left intact (they had entered three) and none of the club teams finished with more than two runners. Forty-two tired, dusty people steered twenty-one tired, dusty, battered motor¬cars into the finish on Saturday, survivors of the hundred or so gleaming machines which left Belgium late the previous Tuesday. Three Alfa Romeos were entered; none finished. Thirteen Citroëns were entered; only four sighed and wheezed into the last control. Out of eighteen Fords only three survived and the entire Triumph, Renault and Rover teams were. wiped out. Volks¬wagens, usually stayers on rough courses, started with seven, finished with one; even the might of Mercedes was reduced from five to two, although two more struggled on till the very last night.

The scrutineering on Tuesday morning was a leisurely affair, and nothing caused much trouble. As last year, there was some carping over lights, the officials preferring paired spot lamps and reversing lights worked by the gear 1ever and not a switch. So while they appeared not to notice Perspex windows and plastic body panels, they banned an odd fog light. Drivers solemnly removed the bulbs, the officials daubed paint here and there, stamped the car and it was over -¬ except for the replacement of the bulbs just down the road. All very casual. One British team chief wryly remarked “You could drive up here in a supercharged plastic van and they'd pass it”.

The cars were despatched from Liège on Tuesday evening (with the exception of eight non-starters including Trautmann (Lancia) and Feret’s Renault) in quick, three-minute batches of three to spend the night on the Autobahn through Germany, arriving just after first light at Neu Ulm, beyond Stuttgart. The section was neutralized for time, but it was here that Rover's misfortunes began. Anne Hall handed over the 2000 to co-driver Denise McCluggage who, while Anne slept, wrong-slotted down the Stuttgart Auto¬bahn and went 100 kilometres before she realized her mistake. The hour’s lateness guillotine swept down on the Rover before the event was properly under way.

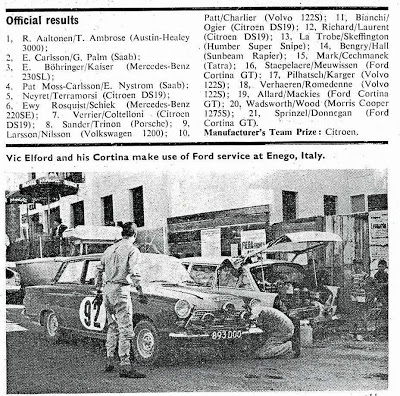

Through Austria, and into northern Italy over the Passo di Resia to the Passo di Xomo, the rally began in earnest. High average speeds were imposed over the dusty, narrow roads, which climbed close to the peaks in everlasting hairpin bends. And the retirements began. The Boyd/Crawford Humber went out before the Alps, so did the Michael Nesbitt/Sheila Aldersmith Mini-Cooper, at Lindau with a broken fan pulley. High in the Alps, at Tresche-Conca the pace and the sun were both hot and tourists coming the other way, through the control at Enego were picking their .way carefully. But enthusiastic Italian policemen waved the rally cars through villages and the popu¬lation joined in urging the drivers to greater things. If the rally was momentarily unpopular with other cars actually on the road, bystanders in those high-altitude villages loved it.

(Below: My 1966 works car on test)

By Villa Dont, just before the Yugoslav border, the WiIlcox-Smith Saab retired, the Xomo had claimed an Italian-entered Maserati, and some really punishing sections began. By the time the rally had entered Yugoslavia and passed through Bled, Col and Carrefour Ogulin in the early hours of Thursday morning the pace was telling very seriously. Ford's troubles began with the Richards/David Cortina going out, followed by the Ray/Hatchett Cortina. The Martin Hurst/Bateman Rover 3-litre retired after a stone damaged the fan, which disintegrated through the radiator. The car lost its water and that was that. The Belgian Harris/Gaban Lancia Flaminia, de Lageneste/du Genestou in their works Citroën, the Wilson/Smith Renault, and the Slotemaker/Gorris Daf, were among the 25 cars this 150-mile stretch of rocky, dusty road claimed. Timo Makinen had persistent tyre trouble; six punctures in quick succession losing him so much time he had to retire and another works Citroën went out with clutch trouble. Both American Ford Mustangs retired on this stretch, one overturned.

Novi, on the coast, Zagreb and the autoput to Belgrade then took their toll. The weather remained hot, wearing out tyres and brakes fast, as well as the drivers. The high speeds on the autoput overheated the gearboxes on the heavily undershielded works M.G. Bs of Pauline Mayman/Valerie Domleo and Julian Vernaeve/David Hiam; both broke before Belgrade. The Clark/Culcheth Rover 2000 stopped with engine trouble and the Marang/”Ponti” works Citroën retired. Many, many cars were now running very late and just before the Bulgarian border the organizers intro¬duced a change of route. This added a loop of fairly easy road about 90 kilo¬metres long, with which went a two-hour time allowance. Whether M. Garot did this to give the drivers some breathing space or not, this was in effect what happened and probably more cars reached the finish as a result. Certainly, the original route was passable (some used it) and service crews at Sofia, the turning point, were glad of the extra few minutes to restore the battered cars to something nearer rallyworthiness.

But Bulgaria claimed its victims too. Renault lost two R8s and Austin-Healey the Paddy Hopkirk/Henry Liddon car, which broke down also with gearbox trouble. Honda, after their tragic Liège last year, had entered one car with a Belgian/Japanese crew, but it, too retired when it was hit by a lorry. The Seigle-Morris/Nash Ford Corsair went out at Sofia and so did one of the big rear-engined Czechoslovac Tatras.

The survivors now attacked one of the roughest parts of the entire rally. Back into Yugoslavia through Kursumlija to Titograd and Stolac. The King/Marlow Ford Cortina (a private entry which usually gets further than most) went out near Titograd after the electrics failed and the car had to be push started at every control. A puncture when the time allowance was running out was the final blow. The Sprinzel/Donnegan Cortina's front suspension was getting tattered by now and needed frequent attention. Help was recruited from the most unlikely sources to weld and rebuild for a harrowing but apparently hilarious limp to the finish.

The Taylor/Melia works Cortina finished, its rally on the same road, or rather off the same road too badly damaged to continue. SimiIarly the Elford/Stone works Cortina crashed with its wheeIs in the air and the James/ Hughes Rover 3-litre stopped against the rocks, thus sacrificing two gold cups. All the accidents were without serious injury to the drivers.

The Gendebien/Demortier Citroën re¬tired less spectacularly but just as effectively with distributor trouble, then it was the turn of the works Triumph 2000s to fail. They had been going very strongly indeed up to Stolac and Split on the return through Yugoslavia, especially the Terry Hunter/Geoff Mabbs car. The Fidler/Grimshaw and the Thuner/Gretener cars went out first, then the third at Split, all within a short dis¬tance of one another with the rear suspension breaking loose. Logan Morrison/Johnstone Syer retired their works Rover 2000 when they went to the help of the Blomquist/Nilsson Volks¬wagen which had overturned. The driver was unconscious and no other help was available (nobody else, not even a VW team-mate had stopped) so Logan's chances went with another car's acci¬dent. The last Rover (the Cuff/Baguley 3-litre) retired, running out of time after hitting a wall near Split. The Toivonen Volkswagen went out with a broken gearbox.

At Obrovac, the rally had spread itself out over many miles of road. The sur¬vivors who were motoring strongest in the intense heat were being led by the Aaltonen/Ambrose Austin-Healey and Böhringer/Kaiser Mercedes-Benz 230SL, bent now and losing oil. The two Saabs were crackling their fierce exhaust notes through the tiny Yugoslav villages watched by wondering peasants and only Ewy Rosquist looked cool at the wheel of the Mercedes-Benz 220SE she co-drove with Schiek, The long, straggling field drove up the twisty, spectacular, but well¬ surfaced coast road beside the inviting Adriatic and back into the Italian Alps for the second time and the final, gruelling night’s drive. Further casualties were few; there weren’t many cars left to drop out and those who had motored thus far were very determined indeed. A Belgian Mercedes-Benz 220SE failed at Bienno and the similar works car of Kreder and Kling at Trafoi.

The finish was almost an anti-climax. Large crowds and flowers greeted the dusty, battered, straggling cars as they creaked into Spa before the final proces¬sion to the Royal Motor Union premises in Liège itself. Past winner Pat Moss and her pert, pretty 19-year-old Swedish co¬driver Elizabeth Nystrom got a special cheer. The winning Austin-Healey looked little the worse for its ordeal and so did the Saabs. Böhringer's Mercedes had lost some front lights. The brave La Trobe/Skeffington Humber Super Snipe whose, performance had been staggering had a dented door; the big, yellow Tatra V8 which had done equally well (such big cars must have been a handful) was similarly bent. The Alan Allard/Mackies Cortina was scraped on all four corners, after an off-the-road excursion on its roof, and the Sprinzel/Donnegan Cortina limped into the finish using up so much of its time allowance that all the crowds had gone home and no one saw its bruises.

What pleased B.M.C. team manager Stuart Turner almost as much as his out¬right Austin-Healey win? “We broke the sound barrier - we got a Mini to the finish of the Liège.” The Wadsworth/Wood Morris-Cooper was, in the final pare fermé in Belgium, albeit with heavy penalties, but after some 3,100 of the world’s toughest, roughest, fastest miles.