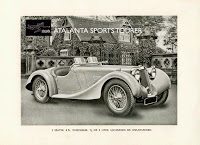

Details of the Atalanta

(left)

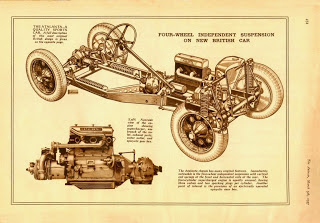

, showing at the International Concours of Elegance at Hampton Court Palace this weekend, are sketchy. It is unlikely to be as avant garde as its predecessor. Only around 20 were made between 1937 and 1939 but it broke new ground as the first British production car with all-independent suspension. Claimed to “maintain true fidelity to its predecessor and offer a unique motoring experience, the new Atalanta exhibits the style of Silver Screen glamour combined with developments from 75 years of motoring evolution.”

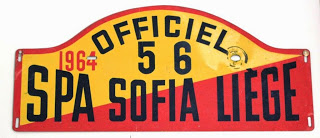

However to match the cars backed by racing drivers Peter Whitehead and Denis Poore, besides novel Hiduminium and Electron all-independent suspension it should have adjustable dampers, hydraulic brakes, two spark plugs with at least three valves per cylinder, and a selectable supercharger. We are told that 90% of the new components are designed and engineered directly by Atalanta, including castings, forgings and fabrications and the body is traditional aluminium-over-ash coachbuilt. But originals had the option of an electric Cotal epicyclic gearbox, a sort of early semi-automatic, or a 3-speed dual overdrive Warner.

The first Atalanta engines were designed by Albert Gough, late of Frazer Nash, and they had more than the feeble 60bhp of the 1934 chain-driven sports cars. There was a choice of 1½litre 78bhp or 2litre 98bhp, but before many were made Atalanta had them redesigned. AC Bertelli of Aston Martin went back to 2-valve heads with superchargers to choice from Centric or Arnott. In 1938 a 4.3litre V12 Lincoln Zephyr engine of 112bhp provided a decent turn of speed. The Zephyr was not much more than a side-valve Ford V8 with four more cylinders, but it improved acceleration. Top speed either way was about 90mph; perhaps more than enough because the independent rear with horizontal coil springs was said to produce curious handling although reducing wheelspin.

(Autocar 1937 artwork above right)

Atalanta managing director Martyn Corfield, who has experience in car restoring: “Staying true to the original Atalanta design principles, we have enhanced the positive and enjoyable characteristics of vintage motoring in a style that is relevant and exciting today. As in the 1930s, Atalanta Motors provides the opportunity to commission an individual driving machine to exacting requirements. The new sports car offers an exhilarating drive with assured handling and a supremely comfortable ride.”

Visitors to the Concours of Elegance will be able to see a prototype of the new car as well as a 1937 Atalanta, one of seven survivors, owned by Matthew Le Breton, which won Best in Show at the 2007 Cartier et Luxe Concours at Goodwood.

“Atalanta’s presence at this year’s Concours affords a rare opportunity to see and commission a piece of motoring heritage.” The originals were expensive at £582. Commissioning a new one will be a bit more.